Rare Books, Rare Writing

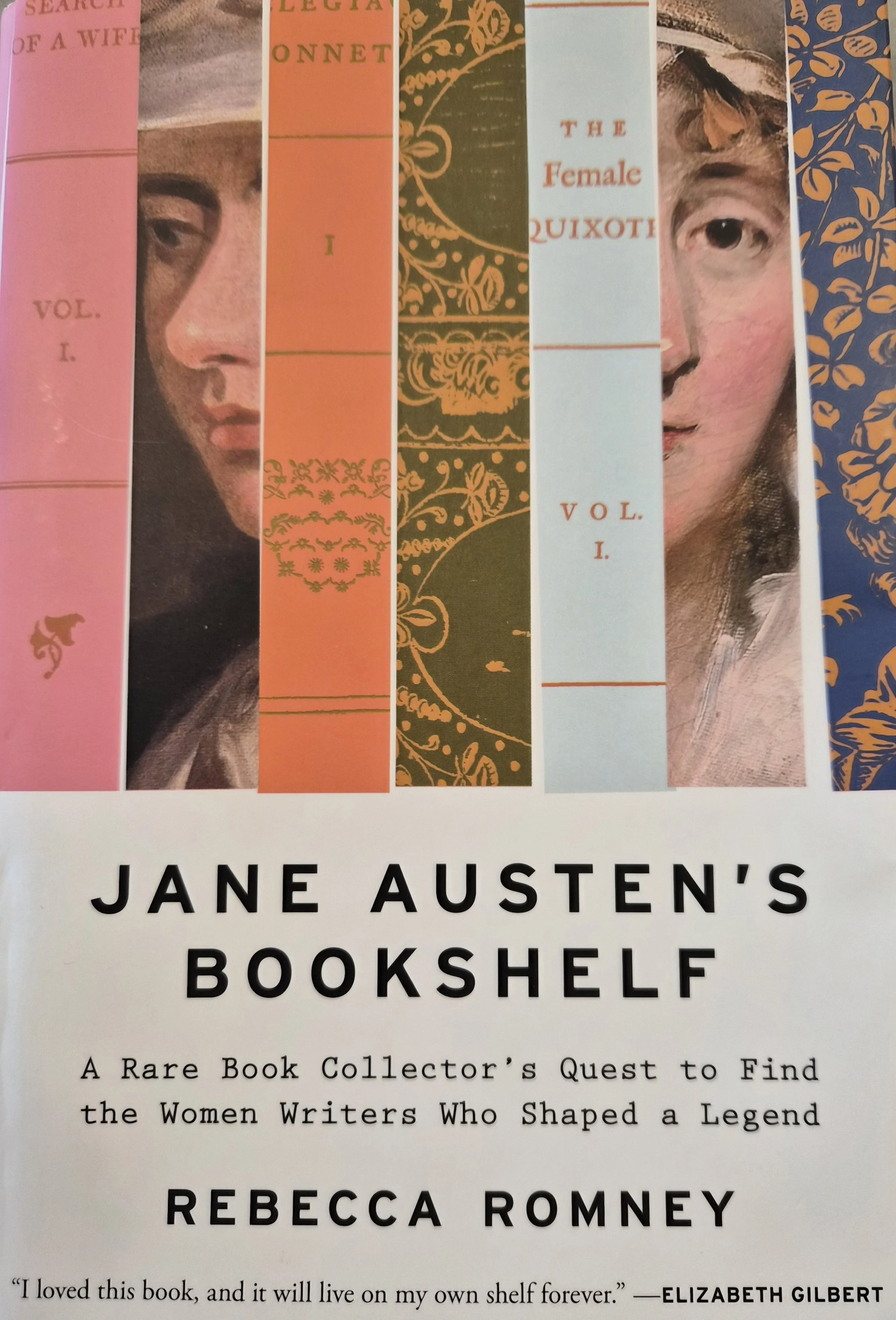

Last time, I spoke of two books that give me joy in the New Year. Read about the first, Sarah Emsley’s The Austens, here. The second, by Rebecca Romney, is Jane Austen’s Bookshelf. Both works are part of the onslaught of at least twenty-five major Austen-related productions for the year 2025, the 250th anniversary of Austen’s birth.

Rebecca Romney is both a lover of novels and a collector and seller of rare books. For her, the “rare” is not just an early or unusual print copy that might sell for a pretty penny but also an historical female writer who is new to her.

Her subtitle reveals all: A Rare Book Collector’s Quest to Find the Women Writers Who Shaped a Legend. There are many such writers before Austen who not only influenced our Jane but who were (mostly) worth reading themselves.

Covered are Austen, Frances Burney, Ann Radcliffe, Charlotte Lennox, Hannah More, Charlotte Smith, Elizabeth Inchbald, Hester Lynch Thrale Piozzi, and Maria Edgeworth. I learned a great deal about Lennox, Inchbald, and Piozzi.

Rebecca Romney takes us on a sweeping tour of early women writers who influenced Jane Austen.

Romney’s theme is what is now called the Great Forgetting—women novelists who were popular in their day but who were later ignored by the male critics who established “the canon.” (The term “Great Forgetting” was coined in 2005 by Betty A. Schellenberg.) Romney tracks the “turning points”—when these women became famous and why, the moment they were shuffled out literature’s back door, and the moment when mostly female commentators brought them back into the limelight.

She covers, for example, Charlotte Lennox (1729-1804), in her day a well-regarded poet, novelist, translator, and Shakespeare critic. Where Austen has wit, Romney says, Lennox has boldness and wit. Of the nine authors investigated, Romney “came to love Charlotte Lennox most of all.”

Lennox’s history in the critical tradition is revealing. She was downgraded mid-Victorian over false and flimsy claims that Samuel Johnson, a friend and advocate of hers, had written a key chapter in her novel The Female Quixote for her. Book dealers have continued such fabrications, Romney points out, because Johnson is much better known. His name being attached to a book helps fetch a higher price in the collecting market.

Romney pulls us along on her journey with the excitement of a gothic heroine working her way through cobwebby halls or damp dungeons, the path lit only by the light of a torch and vivid imagination. (Substitute the excitement of Alice in Wonderland for the dread of the gothic.) Romney treats not only the novels but anything interesting spinning off of them—histories, biographies, other authors—including how Romney tracked down certain editions and why she bought one and passed on others.

Her discussion of Ann Radcliffe, for instance, leads to a multibranched history of the gothic novel, a note that male Romantic poets of the time, including Byron, borrowed from Radcliffe while hiding the connection, and that biographers insisted that she had died of “the horrors” (madness) when in fact she was traveling and living quietly. To Romney, Radcliffe was the “most influential woman novelist in the English language—even more than Austen.” It’s an arresting thought, even for those who may not agree with her.

Austen referenced Frances Burney, likely the most respected female author of the Regency, in her letters in a way that showed her high regard. Over the decades, however, (male) critics set up a duel between Austen and Burney, their commentary designed to “rank rather than reveal,” as Romney puts it. Eventually, Burney was discussed as a diarist rather than a novelist.

Burney’s letters and journals, and her first novel Evelina, are written in the kind of plain, clear language that marks Austen. Burney’s other novels, however, are written in elaborate, ornamental, obfuscatory Latinate language. (Her dedication in a book might be longer than a short Austen chapter.) Burney’s diaries, consequently, are much more compelling. Yet Romney makes a convincing case that the critics presumed that only one women novelist could be placed in the pantheon in any one generation so that Burney must be downgraded relative to Austen.

“A work can be imperfect, so long as it moves you,” Romney says. She is moved by these women writers who have fallen into obscurity. Her rejoicing in her discoveries moves the reader to make their own discoveries. In my case, it was to order Lennox’s The Female Quixote to see how bold and witty she actually is.

---

My book Jane Austen and the Creation of Modern Fiction: Six Novels in “a Style Entirely New” investigates her development as a writer and shows how her innovations as a prose stylist set the course for modern fiction. It is available from Jane Austen Books at a special low price.

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen is also available from Jane Austen Books and Amazon. The trilogy traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions. A “boxed set” that combines all three in an e-book format is also available.

My newest, non-Austen, work is Running Against the Wind: A Black Arkansan’s Pursuit of His Dream, which describes how a black man’s pursuit of happiness remains difficult and even dangerous in America today. Available from Amazon.