Two Women, A World Apart

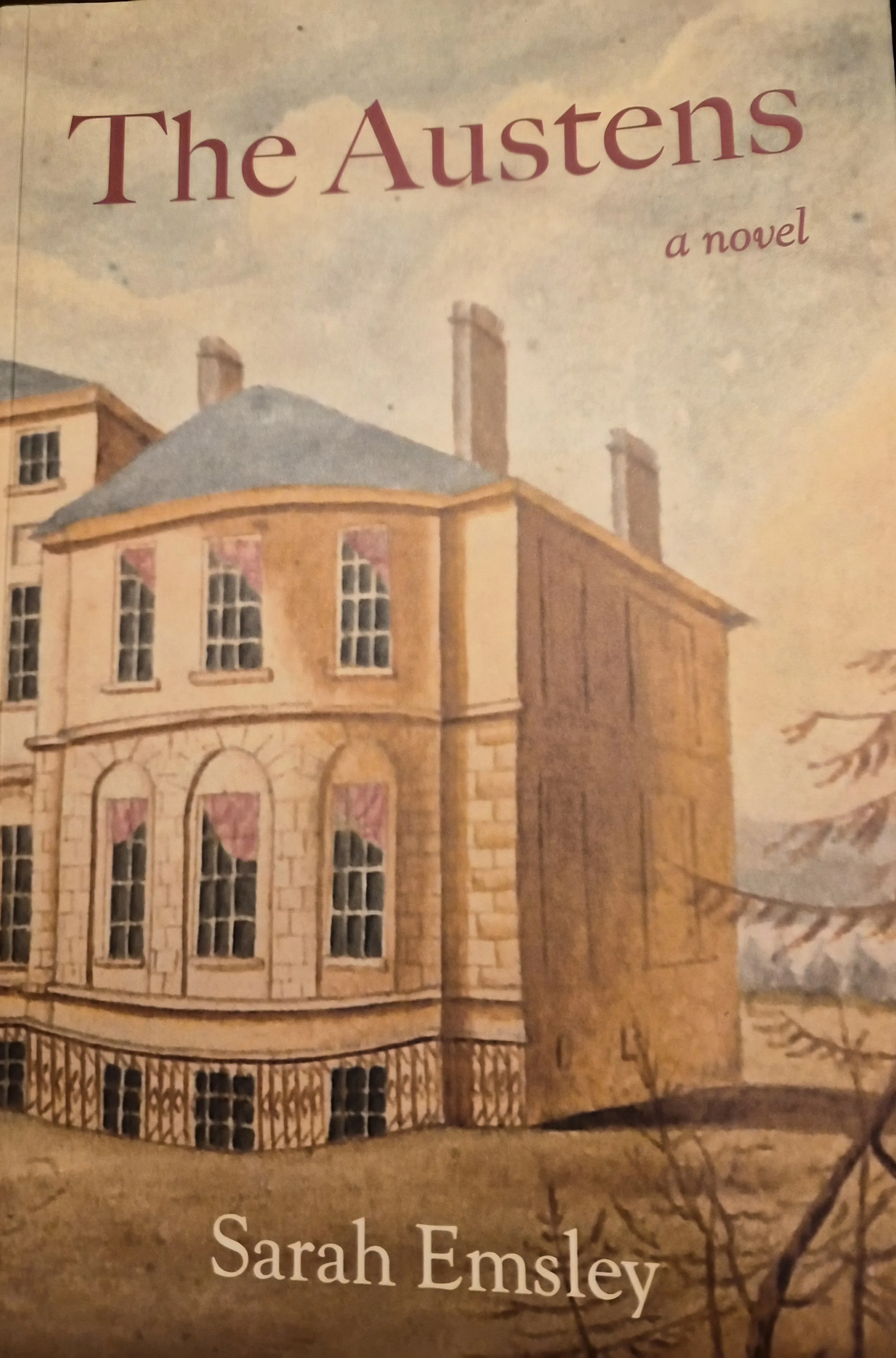

Two books give me joy in the New Year. The first, by Sarah Emsley, is The Austens, a novel about Jane Austen’s relationship with her sister-in-law, Fanny Palmer Austen. The second, by Rebecca Romney, is Jane Austen’s Bookshelf, nonfiction about women writers who shaped the English author.

Both works are part of the onslaught of Austen-related productions for the year 2025, the 250th anniversary of Austen’s birth. At least twenty-five books on Austen and her family were produced in the year (per AI search), and no doubt dozens of other books of Austen-related fiction came to press as well. Emsley’s The Austens and Romney’s Bookshelf are notable for their originality, their research, and their generosity of spirit.

I’ll focus on Emsley here and treat Romney next month. My initial effort to combine them in one blog led me to short both.

One reason for my interest in Emsley’s The Austens is that she and I are the rare writers who chose Austen as the subject of our fiction rather than one of her characters. We also picked roughly the same time period and some of the same events, as best they are known. We created comparable, if not similar, scenes and letter exchanges. The physical distances between characters enabled us both to alternate regular narrative with the novel-in-letters style, paying homage to the epistolary, a favored form of fiction in Austen’s day.

We also set out to achieve similar purposes. In her Afterword, Emsley says she wanted to know “what happens after the happy ending” in Austen’s novels. She wrote The Austens “to explore this question.” (On the first page, Austen is challenged: “why do you not write what you know to be true?”)

In my trio of novels, The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen, I also sought to explore life after marriage. I put Austen in a new, though a plausible and possibly even likely situation—a hidden relationship lost to history.

In contrast, Emsley builds a relationship between Jane and Fanny in a way that illustrates each other’s character and the reality gap between married and unmarried women in the early 1800s. Emsley's novel and mine end other than Happily Ever After, both requiring Austen to reassess her fundamental values and understanding of life.

Sarah Emsley's novel The Austens captures the compatibilities and conflicts between two different intelligent, spirited women.

Emsley spent eighteen years writing and revising The Austens. The care shows in each well-crafted sentence. Nothing stands out, and everything does. Coincidentally, what Romney writes of Austen in her Bookshelf applies to Emsley as well: “Her style has the ease that comes from an incredible amount of work.”

Spanning 1802 to 1814, The Austens opens with parallel stories of the lives of the older Jane and younger Fanny on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean. We see Jane struggling with early literary hope and rejection, a marriage proposal as recounted by the family (but curiously never proved in actuality), and the death of her father and consequent poverty. We see Fanny entering into the teenage years with all the hope and excitement of a genteel girl of that age. Their separate experiences slowly converge.

Fanny was the youngest daughter of the attorney general of Bermuda, her story first explored in depth in Sheila Johnson Kindred’s biography Jane Austen’s Transatlantic Sister. In my view, this was the best Austen book of 2017. Only seventeen, Fanny married the dashing young naval officer Charles Austen. The youngest Austen sibling, Charles followed older brother Frank into the Royal Navy and took his first command, of the sloop Indian, when construction was complete in Bermuda in 1805.

Emsley goes beyond Kindred in using fiction to capture the spirit, the doubts, the growth of the young, bright, naïve girl-then-wife as she struggles to adapt to marriage, motherhood, onshore and on-ship living, and the requirement to quickly navigate naval hierarchy and politics and jealousy of another woman.

Emsley wanted sisterly relationships rather than romance to take center stage. She achieves her goal through exchanges between Jane and her sister Cassandra, Fanny and her sister Esther, and of course through letters and conversations between sisters-in-law Jane and Fanny over nearly a decade. Each pairing of women carries a different tone and rhythm to reflect the respective personalities and relationships.

(Romance is not entirely ignored. Charles and Fanny manage passionately discreet private moments now and again.)

The couple alternated life between Bermuda and Halifax, Nova Scotia, for five years before Charles was finally reassigned to England in 1811. Fanny joined Charles on five 740-mile voyages, often difficult ones, each way. Two daughters were born in North America. That is, Charles developed a bustling new life and family long before any of his Austen family, including Jane, ever met them.

Much as Mansfield Park’s heroine struggled to adapt to the changes in her younger brother after years at sea, there exists an underlying sense that on Charles’s return the Austen family may still regard him as the kid brother rather than as a seasoned naval officer who has demonstrated bravery in multiple battles at sea. (And who remains poor because his naval prizes—captured ships and cargo—do not amount to a great deal.)

Emsley envisions Jane and Fanny initially becoming close at a distance as a result of Jane’s reaching out via overseas correspondence. When they finally meet in England, the differences in their lives and temperaments alter their view of each other, creating friction.

Fanny laments to her sister that Jane shows “more kindness in her letters than she does in person.” Implicit, too, is the possibility Jane may not fully credit a younger woman who endures more in one year of married, motherly naval life than Jane has endured to date in all of her unmarried, unpregnant adulthood.

By Charles’s return, Jane is living comfortably in the Chawton cottage provided by rich brother Edward, jazzed at the imminent launch of her first novel, Sense and Sensibility. Meanwhile, Fanny and her kids, to save money, live aboard Charles’s new posting, the worn-out Namur, which is anchored fulltime in a defensive position at the mouth of the Thames.

Claustrophobia, a lack of social contacts, and constant seasickness create daily vicissitudes for the young Austen clan. Their girls rotate out to stay with her parents in London, where they moved years before. When they do visit the Austens, Fanny deals with fussy babies, spilled food, and related infant carnage while Jane holds her head in pain at the commotion.

Virginia Woolf once said that it is hard to catch Austen being great, which I interpret to mean you can’t easily point to one great scene or one stretch of stunning language to illustrate her genius. Rather, it’s in the steady buildup of moments and details.

The same analysis applies here. Emsley gives us no sudden shocking insight or plot twist or “Aha!” moment. Instead, she carefully layers in the conflict as Jane struggles to understand a woman who is literally from another world and Fanny struggles to be treated as an equal in a household of strong, brilliant characters—and to have her husband treated with the respect he deserves.

At times, and not unlike the other Fanny in Mansfield Park, envy seeps out of this Fanny at Jane’s comparatively easy life.

These subtle interactions between the two intelligent women create surprising force. Susan Allen Ford, respected editor of the Persuasions journal, was so captivated by the story that she read The Austens on her front porch in one day.

Austen was once described as standing as straight as a fireplace poker. I’ve taken that to describe her prose as well: polite, disarming irony underlain with iron strength. Emsley too uses the quiet, unassuming language of a Regency lady to cloak a ramrod prose.

___

My book Jane Austen and the Creation of Modern Fiction: Six Novels in “a Style Entirely New” investigates her development as a writer and shows how her innovations as a prose stylist set the course for modern fiction. It is available from Jane Austen Books at a special low price.

The Marriage of Miss Jane Austen is also available from Jane Austen Books and Amazon. The trilogy traces love from a charming courtship through the richness and complexity of marriage and concludes with a test of the heroine’s courage and moral convictions. A “boxed set” that combines all three in an e-book format is also available.

My newest, non-Austen, work is Running Against the Wind: A Black Arkansan’s Pursuit of His Dream, which describes how a black man’s pursuit of happiness remains difficult and even dangerous in America today. Available from Amazon.